Lenses: Guidelines – ranging from general design to specific disciplines; some more refined than others, but none perfect.

These can have a variety of applications, whether it is:

- The most common use – analyzing another game

- An ace up the sleeve, when stuck designing a particular feature

- Gaining focused pointers to build upon

- Or my favorite, merely refining the design

That said, the application and the context vary the output from lens to lens.

The Lens of Emotion by Jesse Schell – unlike some other lenses – stays true to the cause of us designers – creating a more magical experience that stays transparent to the player; rather than merely taking advantage of the psyche.

This lens is better applied to building specific features – rather than the underlying experience because the answers are clearer in that scenario, as you want these emotions to be situational. However, you can also apply this to the game as a whole to dig deeper into what you want from the game, and what the game wants from you; then achieve this in each applicable design category.

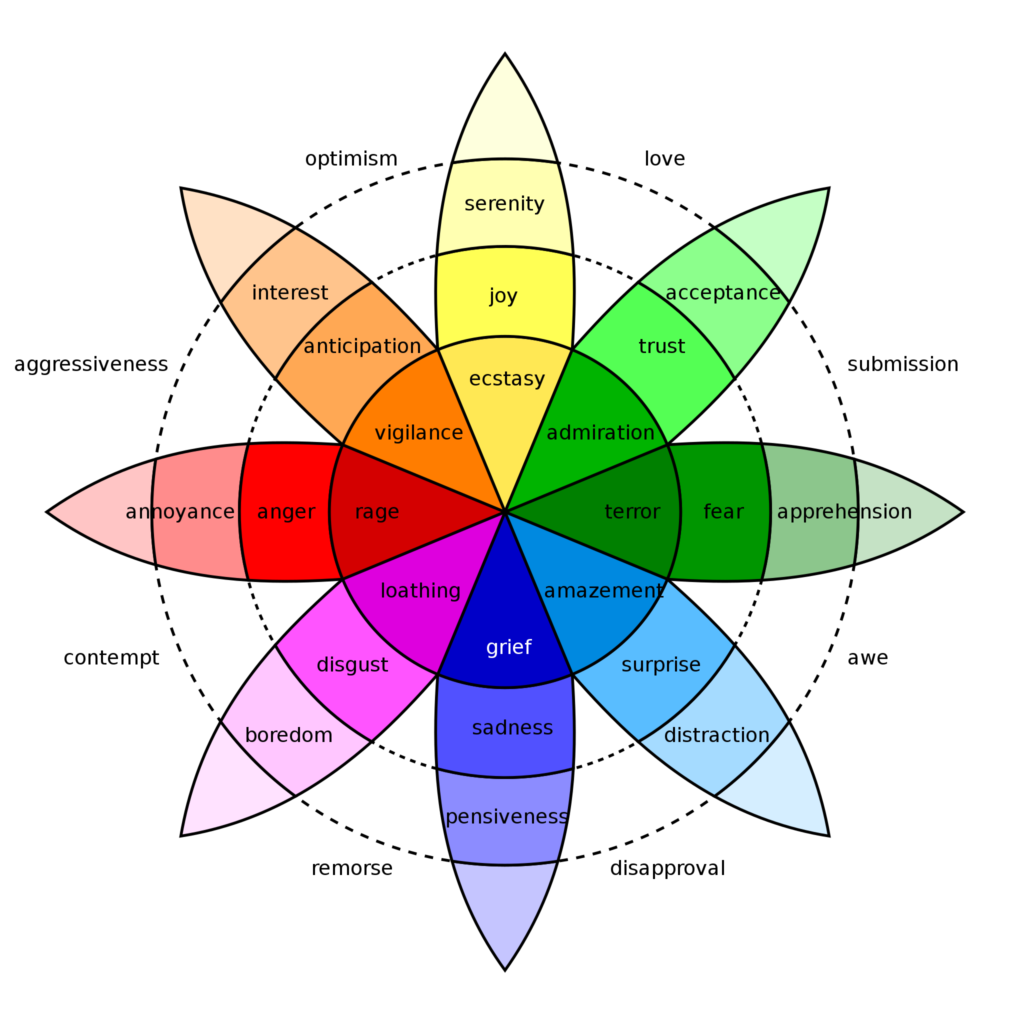

That said, without a reference point, one may struggle to search for answers demanded by this lens – on certain features. That is where the Wheel of Emotions by Robert Plutchik comes in.

Use both of these in tandem for killer design output.

Let us consider a horror game as an example application. Mixing the inability to fight back, with the suspense of low enemy awareness stays true to the horror genre by introducing fear in the gameplay. This also means that the void left by the buffer to the death condition needs to be filled up. One approach is to position oneself away from the enemy. Therefore, the player needs to react pensively to the feedback cues – which could be further divided into many prominent and subtle cues.

There are other models pertaining to emotions: some simpler, some complex – but I’ve found this to be the sweet spot.